Writing the Runes

Yesterday's first tentative step into defining the Gyldland Runic alphabet - now literally carved in stone - got me motivated to scribble down the foundations for a full set. (Of course the set need not be complete and accurate, given that researchers and archaeologists - of fictional civilizations as well as real ones - can only analyze what they have found to date, and so different inscriptions from different times will no doubt have variations on the 'basic' set).

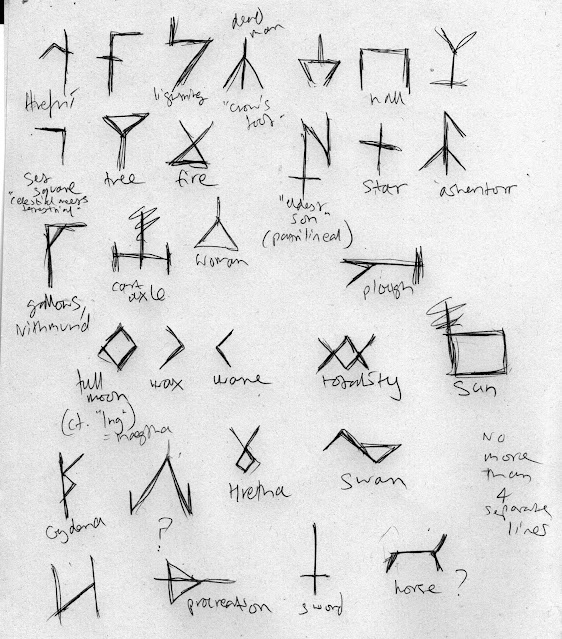

Because so much quasi-mystical nonsense has been written about Runes in recent times, I actually have very few texts pertaining to them specifically, but drew inspiration from the Anglo-Saxon Rune Poem (in 'Anglo-Saxon Mythology, Migration and Magic' by Tony Linsell), Rudolf Koch's 'The Book of Signs' and Maria Carmela Betro's 'Hieroglyphics: the Writings of Ancient Egypt' in creating a rough selection of individual symbols - some of which clearly still resemble their earlier, pictographic associations:

Being able to represent all six of the primary gods was a good start, with the three lunar deities Maegtha, Hretha and Haegena defined by their lunar phase schematics, while Nithmund, the grim rat-god, is simply a gallows. I suspect the meanings of each symbol are deep and relevant indeed, allowing them to be used in divination, curses and prayers, and like Tarot cards can be inverted, flipped and re-ordered to vary or reverse their meanings or intentions. Given that, I reckon some sort of base-line (defining the top and bottom of the inscription - "This way up") would be essential: a prayer-sequence seeking good health and cut into a piece of wood could easily be inverted by an evil-minded one to bring sickness instead. In this way the recipient knows the original meaning of the message, no matter its eventual orientation, and 'casting Runes' would allow the symbols to land in whatever configuration fate decrees.

As to how this human set differs from the Ulfish tradition of Rune-carving, I've yet to discover. Ulfish Runes are unique, as an academic footnote recorded elsewhere explains:

"...the unique character of Ulfish rune-carving, wherein the physical depth of the incised staves (always inscribed onto wood – their written chronicles are large panels of ice-birch) embodied additional levels of meaning, accent or emphasis within the inscription: similar to, but more nuanced than, bold face or italicized script, and therefore capable of rendering many texts virtually untranslatable into other tongues. A smiliar technique is found in Sli’ith script, where the length of medial and final characters can emphasize – or de-emphasize – the attributes of a word’s meaning."

(Chapter XVIII)

Elsewhere, in terms of the value of writing and therefore learning, Gifli speaks of when he

"Spent fifty summers in a hall

with others like myself, to learn

as many things as in the worlds;

the stories, songs, and tales of old;

histories and royal lines,

the fate of kingdoms, dynasties,

recipes and charms and lore.

Some say – why fill your head with stuff?

But fires burn and moth-worms chew,

armies raid and thieves may steal –

then, skins and books are gone for good,

and thus their wisdom, wit and joy.

And learn we did, to hold in thoughts

those books we spent our days within.”

(Chapter XLI)

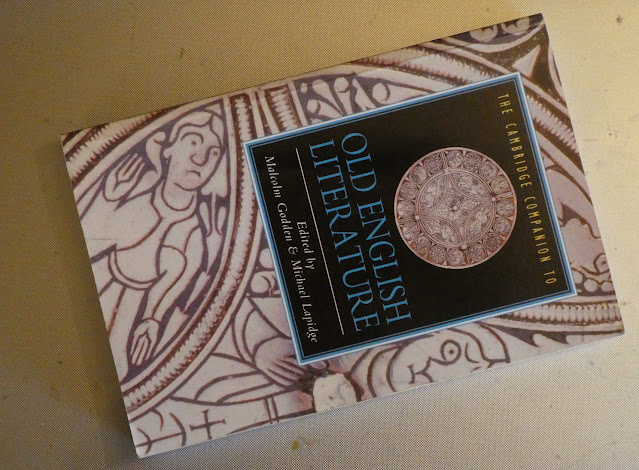

This sounds to us very like an early medieval monastery scriptorum, but in reverse: almost a parallel to Ray Bradbury's 'Fahrenheit 451' - the moth-worms being a reference to the Exeter Book riddle number 47, and the raiders and thieves clearly Vikings in another form; book-burners, certainly. The disparate collection of things learned also reflects the often varied contents of the various OE manuscript collections, and begs the question of why certain things were deemed worthy of recording. Books are clearly superior, more portable and easier to create than laborious stone or wood engravings, but also more fragile. As to how the most 'up to date' form of Gyldland Rune-writing, devised for book-script rather than more primitive carving, varies from its elder form, I'll no doubt figure out later when I try it myself (but I'm assuming distince variation for initial and medial forms of the same characters, to allow for a more fluid calligraphy, though without the celebrated Arabesques of the Rockcat script).

A pivotal scene occurs when Gifli, in his insatiable curiosity and love of books, devours Womba's copy of her father Deor's diaries:

"“You did know, did you not, my friend,

that in these texts are hidden things?”

But Womba, puzzled, shook her head.

“What’s hidden, how? It’s tales, and lore.”

Gifli raised a page on high, said, “Look.

Observe the candlelight herein.

See there – there’s runes, between the words,

in secret ink, but now revealed.

The tongue is old, though known to me;

a version of the Fealleth speech,

once-common on the shores of Yeow,

though makes no sense at all, as yet;

I think there’s more to be unbound.

As I find more, I’ll let you know.”"

(Chapter XLI)

The interwoven runes in a foreign tongue suggest the Runic riddles lefyt by Cynewulof in his poems - word-puzzles to be solved by the reader. As Cynewulf's runes spell out his name, and therefore the identity of the soul for whom the reader is beseeched to pray, so Womba's texts contaian the path to her own destiny, a treasure map of individuation, no less.

Text and language in all its forms, again, prove to be the axis points of the whole work.

Comments

Post a Comment