Geometric art, Climate Change and Extinction

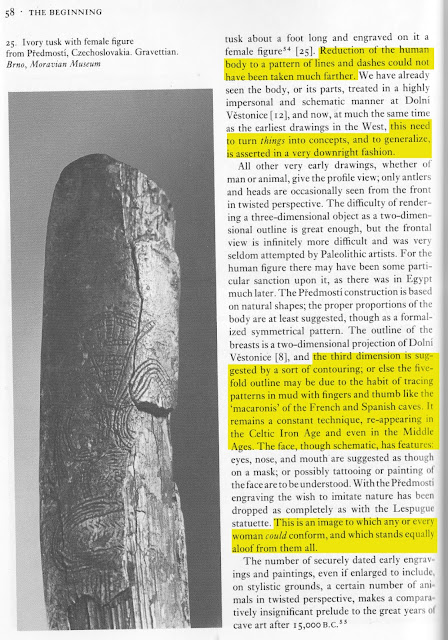

While reading through N.K. Sandars' Prehistoric Art in Europe has so far been hugely stimulating, as previously posted, the above page in particular drew a number of things to my attention: considerations of different forms of representation, in this case, the geometric, even abstract, depiction of universality of form; but also the idea of finger-art, which may be the oldest form of sentient art imaginable, if we consider an appendage tracing hesitantly in sand, clay or snow - an action which is, in the poem, defined as the origin of the written form of the Rockcats' language, Sli'ith, and its cursive nature (which, visually, is suggestive of Arabic script):

"Few men could write, but Rockcats long

recorded words in their tongue, Sli'ith;

and unlike rigid runes, their writing

flowed in curling twists and tails,

for once they wrote their words in sand,

when on the coast of Kren they stood;

a new-born people, elder tribe;

those ancient days when all were one."

(Chapter VII)

This thought turned me back onto my previous history of working in clay, and seeking new ways of approaching its use: perhaps a number of 'ancient clay fragments' from the earliest days of my mythical world? The very form in itself - the clay tablet - suggests a different time and place to that depicted in the poetic narrative, namely one of near or middle Eastern character. And that in itself suggests a significant case of climate change - from a warmer, even desert environment, to a harsher, colder, more North European system over unknowable epochs of time. With climate change an ongoing issue not only in the present day for us, but for our earliest ancestors whose work is detailed and described by Sanders, this fits nicely into my broader themes of ecocriticism and dark ecology, and suggests a time when my world was very different, and whose shifting ecosystem has moulded the world into its present form. In fact, the clay remnants and fragments of this elder culture (the gods? the dragons? the first sentient races?) would be archeological residue of a different world, as inaccessible to my characters as Ice Age environments are to us. However, climate catastrophe could return us to it - in the same way that certain events in my mythical world could once again induce apocalyptic scenes which would literally move mountains and turn whole lands to ash. These fears have already been written into the later scenes which approach the climactic ultimate battle, but will now be echoed elsewhere as a recurring warning of what really is at stake. Such a shift may even be the logical outcome of a limited number of elemental climate shifts: from earth (desert), to water (ice), to wind (storms), to the future of a fiery, dragon-induced (?!) apocalypse...a premonition of which is uttered by the Ulfish seeress on the eve of the showdown:

"“Thus speak the seers from ancient days,

the eyeless ones of Ash-staff’s roots,

whose words have passed from mouth to ear:

the end of things, the crash of doom,

when time is ended, worlds broken:

gods devour gods, men devour men1.,

and beasts devour the cold remains;

when entrails swollen encircle the worlds

and seas spill over deep with blood;

burgs of bones cast shade on mountains.

Total war, a lifetime long,

will rage upon the reddened earth –

til none remain. The skies held still.

No wind, nor hail, nor tempest blown –

the air itself choked of its breath,

and darkness, ever-strangled night,

eternal, endless, evermore –

a gallows for all that ever was1.

The wolves of waste shall be well-fed.”

She bowed her head, and silence sunk.

“It need not be,” cried Sigfri loud, at last;

“While wyrd has stopped, it seems, for all,

we can now choose to make our own.”

“Whether now or hence, the end will come,”

Kra-hrarr replied, “But, fight we shall,

for that is what we live to do,

we children of Ulwarf the King.

The lords prepare, our forces wait.

Go do the same; I’ve rituals due.”

She stood, bone-creaked, stooped, and went.

And Sigfri sighed, and left that cave."

1

HR

Ellis notes te lack of reference to the humanity at Ragnarok legends

– herein the mortal races are barely even mentioned, being an

insignificance to the cosmic cataclysm which creates a nihilistic

anulling of totality – a reduction to nothing, wherein all

existence ceases – an

unthinkable, unimaginable inversion of reality and being in the

broadest sense.

The Ulfish sense of fatalism is of course derived from the Old Norse eschatology spoken of in the Voluspá, although the concept of those without optical sight having greater inner sight or wisdom, is one that has a certain universality - not just within the poem (the seers of Gifli's people, the Bhukkoni, even put out their own eyes that they might enhance their wisdom by binding scrying 'serpent-stones' into their empty sockets instead) but in myths such as that of Tiresias.

As Eugene Thacker notes, "Extinction is always speculative. Ray Brassier encapsulates Kant on this point, noting "extinction is real yet not empirical, since it is not of the order of experience."" (E. Thacker, In the Dust of This Planet, p. 124). The prophecy is imitative of Thacker's world-without-us - a world of total annihilation of all that has gone before. After the events of the Old Norse Ragnarök, the few surviving gods get together and talk of the 'old times', of things they knew (and could remember) from the previous age. They find "in the grass the golden playing pieces that had belonged to the Aesir" (S. Sturluson, Edda, Everyman, p. 56). Thus relics - fragments - and oral memories, the substance of human myth, remains of an older time, persist; but via the interpretations and prejudices of the new custodians of this knowledge. Perhaps my developing concepts of 'clay tablets' of prior civilisations suggest an equally cataclysmic end to a previous world...the 'new world' being one in which my shamanic wanderer, Hrefni, finds himself set up as god of storms, along with his exogamous consort, Gydena...

The vigorous depictions of animals, and bison in particular (as above) throughout Sanders' study, also inspired me to consider - again - the motif of extinction, previously discussed in an earlier post on land and ownership. The long-gone ice-ox certainly suggests a creature from an intermediate ice-age world between the earlier, desert environment and the current one inhabited by the main characters as schematized above, and made me wonder what such an animal mght look like, or what it meant to the characters' ancestors. Surely they would have depicted it in some form - and if so, what? Something like the famed French cave paintings and sketches, or entirely different?

My original plans for depicting the visual aspects of this work centred around wood and stone, but new media have sudddenly presented themselves, and I'll soon be working on the first experiments in these areas.

Comments

Post a Comment