Literary Influence and Development: a Few Examples

|

New addition to the ever-growing library arrived yesterday: The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature, primarily for J. D. Niles' often-cited essay Pagan Survivals and Popular Belief, which covers many areas of folklore in the Anglo-Saxon period, although the other contents look to be invaluable in terms of background research, also. One of the most exciting aspects of writing this epic poetic work - and developing its background and narrative themes - is its sheer dynamism and fluidity, where new research, interests and readings have been able to feed directly into its development and suggest new directions, stories, parallels, and reference points, especially those gathered through the Old English Texts Semster 2 Humanities module.

For example:

The Ruin directly influenced the ubi sunt nature of the heroes' arrival in the land of the Ylfu, (the elf-like race who have lived in voluntary exile beneath the earth for countless generations), and exposed the illusory nature of their own self-delusions;

"'These city-halls were sun-bright once;

high endless spires, gabled roofs,

mead-halls many, walls of might.

Where are the blazing roofs of gold,

where the brazen rails and vanes?

Where stand the columns, where the statues,

whose heads were crowned by cloud and sky?'”

The Seafarer, as mentioned elsewhere, clarified the ideas of exile, loss, and longing for those outside the society of the hall and its social comforts and ordering system - a perfect angle with which to approach the exile of the large body of main characters, driven from their homes by evil forces and strife, and forced to wander the seas as a people in exile (from the King downwards) - therein, the Biblical connotations became clearer, too.

For example:

"Past empty islands then they sailed,

the Gyldland folk, the Ulfish bands,

braving wind and rain and spray

and swirling pools where sea-wyrms dwelt;

in soaking, sullen, silent journey

in hope that hearth and heat may once

be found again, and life restored;

to sit in hall, with lord and mead,

with few hardships to bring forth care,

the city’s comforts full and well

before the time of troubles came,

the deeds of ice-born lords their doom,

all life’s worth then squandered, lost,

made ash by wyrm-fire, sword and hate.

Travelling turbulent whale-tracks, weather-worn,

harried by hail and wind-whipped sore,

ears burned and nipped by Wedri's breath,

eyes red and wet through night and day

where sleep was soiled by stabs and pains,

the sea's thrusts knotting, wrenching guts

such that bold kinsmen, Ulfs and men,

shaken in limbs, spewing over side,

met the dawn's clash with little courtesy;

the rays of Soli faded, fog-thinned,

grew dark under night's hood; day-shine dimmed." (Ch. XXXIX)

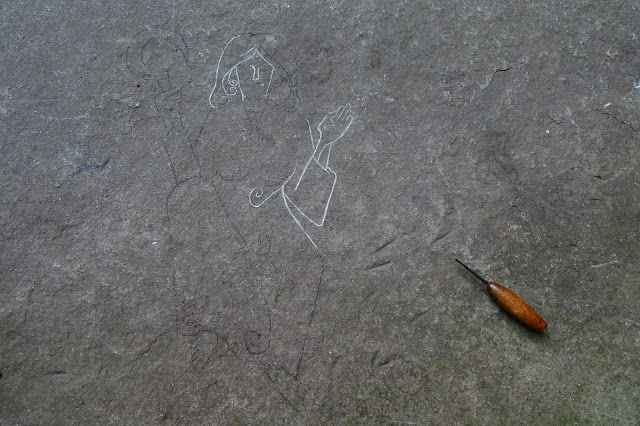

The Exile of Guthlac lent many features to the narrative detour of Womba's decision to part company with all her people and allies and return to the barren fenlands from which she came, a sequence which deliberately invoked the imagery and language of anchorite life in a liminal, threshold environment, which lends Womba a saintly dimension: giving up her own comfort and security for the greater good of her people. And like St. Anthony, she is continually tormented by the coven of thirteen witch-queens of Nithror, whose goal at first seems to be mere harrassment - until the true nature of their 'testing' of this heroic soul becomes clear.

Deor and Widsith suggested poetic devices; a refrain from the former, and the notion of a narrator who embeds himself in multiple narratives across time and space, more than any single life could accomplish. My narrator, Sigfri Far-Treader, had already been defined as an ageless wanderer, with vague allusions to the character of Odin/Woden (see B. Branston, The Lost Gods of England, London, Thames & Hudson, 1957; p. 104 for a wonderful evocation of the singularly English character of Woden), but the analysis and theory of Widsith as a 'named poet' allowed me to develop this aspect of his role further. Deor, being probably the only poem in OE with a true refrain in the modern understanding of the word (Wulf & Eadwacer is debatable), suggested a recurring 'cut-away' snapshot of the gods' reactions to the preceeding action of each individual book: a refrain which begins at the close of Book I as

"And up high in Heofenroost,raven-cloaked Hrefni watched, and worried"

and evolves more detail as the narratives develop towards their inexorable climax.

These examples are enough for now, but I look forward to what new angles of approach might be derived from this weekend's forthcoming reading.

Comments

Post a Comment