‘The Language of Myth, and The Myth of Language’

What's this all about?

Basically, the documentation of my 2021 final project for my MFAAH Master's degree.

“Myth is a type of speech” (R. Barthes, 'Myth Today' in Mythologies).

If my work has a narrative, then it is one of narrative itself – sometimes multiple narratives, sometimes competing, unreliable, questioning, contradictory, and ambiguous. At times, meta-narratives; stories within stories, inside re-tellings of tales perhaps familiar or else new. And one of my most cherished kinds of ambiguous narrative is myth.

Myth, as an oral body of knowledge initially, is therefore speech. And in written form, embedded, it is capable of being analysed, quoted, paraphrased, interpreted, mis-interpreted, bastardized and corrupted.

The language I use to disclose my myth-makings are related, though separate; at once distant and unknowable, yet simultaneously tangible and everyday: English, and its antecedent, Old English – in which copious amounts of our modern English (and Scots – being of shared Germanic heritage) words originate, providing a bridge of familiarity to an unfamiliar culture.

In Old English literature we find oral works committed to writing – the final and only knowable forms that we, 1000 years later, have to analyse: “To the Anglo-Saxons, stories, riddles, songs – the wisdom of a people – was carried mentally, orally, in the word-hoard or ‘treasure house’ of words, the individual and collective memory of the tribe” (Craig Williamson, swarthmore.edu). In the writing I am producing, real language blends with mythical language – the speech of imaginary tribes and beings – as well as the language of myth, where tales of gods and heroines are woven into the ambitious narrative.

Namely, a work of epic poetry, simultaneously subversive to the conventions of that form yet also respectful of its representatives; and a mythographical, iconographical series of images of how the inhabitants of that poem’s world might have imagined their cosmos. Written in modern English, the poem presents itself as might a translation of a genuine text, with claims to keeping the tone and poetry of the original – the use of kennings1 proliferates with the brevity and qualities of allusion, double-meaning and the ambiguity inherent in Old English.

Dressed up as ‘high fantasy’, it nonetheless addresses real-world contemporary matters: gender roles, non-binary selfhood, eco-criticism, propaganda, historical colonization, the ‘world for itself’ and ‘world without us’ theories of Eugene Thacker2, and how historical narratives, and therefore the present, are (re)constructed. The poem plays with mythology; poems interpolate into the main narrative; characters bear multiple names; ‘point of view’ is a mobile concept. Recurring themes include the need for unity and exogamy – a critical source of myth as discussed by Levi-Strauss and Freud, via the incest taboo.

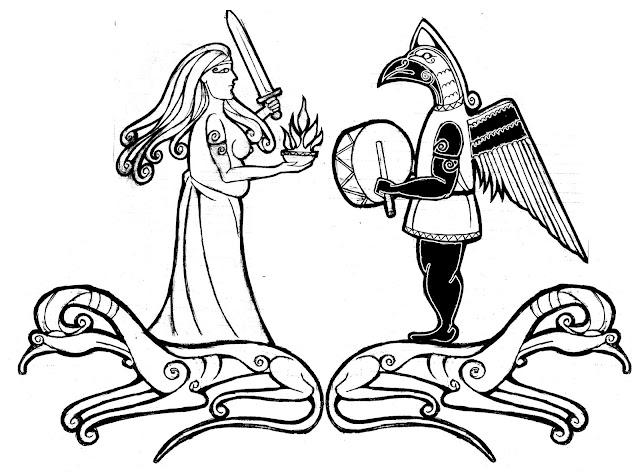

As the framework of the poem is an artificially-constructed myth system, this gives rise to visual representations of gods. Levi-Strauss describes ‘primitive’ art as a system of signifiers which connects the tribe to its supernatural beliefs, and which limited tools and materials can construct only as a visual language for its originating culture. My designs are amalgams of the local (Pictish stone carving) and Old English manuscript illumination, with aspects of native American and Mesoamerican representation in an attempt to evoke a tangible yet foreign culture. One example is the primal beast who is dismembered to create the cosmos and later restored as two separate creatures, who then beget all animal life [see Illustration 1]. This creation myth gives animals their separate and parallel genesis, allowing animal nature to live ‘for itself’, in reference to Thacker. These designs are modelled on the Pictish ‘beast’ which has been variously identified as giraffe, elephant, fish, kelpie, dolphin and horse [see Illustration 2]– its very ambiguity informing my use of it as a universal. My beast’s deer-like form is a reference to the OE deor3, which became ‘deer’, but originally referred to any wild animal.

Language itself becomes narrative; the poet’s rendering is, like any retelling, faulty by definition and cannot render unto us the calligraphic sweep of the Rockcats’ Sli’ith, or the physicality of Ulfish rune-carving. Borge’s Garden of Forking Paths reminds us of the power of the editorial voice, which even supersedes that of the narrator’s. Speech becomes mythical: ancient characters converse in a tongue drawn from Proto-Indo-European lexicons (namely Julius Pokornoy’s compendium). The shamanic storm god, Hrefni, owes his name to the OE word for ‘raven’ - simply a reflection of the poet’s own cultural and linguistic origins for the raven features in multiple world mythologies as a semi-divine solar messenger, and is a culture hero to the eastern forest native Americans. In reality, shamanism originates in Northern Asian and Ural-Altaic regions; thus Hrefni may himself be a migrant from distant tundra. Disregarding Georges Dumezil’s Indo-European tripartite structure4, my divine lineage is rather a spectrum of light to dark in which the goddess of the sun comes first, and whose centrepoint is hermaphroditic Hretha (a subconscious re-imagining of Eliphas Levi’s Baphomet – [illustrations 3 & 4]) and who is cited via ‘they/them’ pronouns (cf. William Blake’s ‘Ololon’ who is also referred to in such terms).

CONCEPTUAL AND THEORETICAL REFERENCES

After Semester 2’s intense studies of real myth, I set out to create a mythology of my own. To carry this, I chose the epic poem as a vehicle; ostensibly a tale of grand battles and heroic destinies, but via a world-view that embodies alternative and subversive modes of thinking, encouraging the reader to think laterally, and reconsider attitudes taken for granted in our world: Who owns land? Whose history (or mythology) is ‘right’? Why do we assume our morality is the correct one, and what is our place in the cosmos? What can legends and literature tell us about their tellers, and ourselves?

My S2 Humanities module Old English Texts heavily informed this work: themes of exile, loyalty, elegy and dream-vision in OE poetry gave me a literary corpus to ground myself in and ultimately take flight from, with analogues in The Exile of Guthlac, The Wanderer, The Ruin and Beowulf so that the work becomes symbolic of the cultural and literary mindset which devised that corpus. Through the ‘heroic’ poetic model – born from the hypermasculine comitatus culture of the Germanic mind, I re-colonise the world of the epic with characters and events counter to later propagandistic distortions of these aspects of English (and north European) literary heritage. The setting presents a world that is at first familiar: kings rule, men glorify battle, and swords are treasured heirlooms, but how might this world be viewed through the eyes of a non-human, non-male, non-heroic character, who – through fate – is nonetheless called to become heroic? The poem takes up the challenge of Cixous’ manifesto of écriture feminine: “Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies... Woman must put herself into the text – as into the world and into history – by her own movement5”. Female characters in the Germanic heroic canon tend to be presented as either passive peace-weavers (Wealhþeow) or as baneful disruptors of the comitatus (Modþryðo, Grendel’s mother): “The image of Old Norse women...can often be reduced to a simple dichotomy of ‘powerless’ and ‘powerful’, ‘good’ and ‘evil’...6” and whilst not myself female, I aim to create a number of nuanced female characters, the like of whom never appeared in actual heroic epics and whose actions drive the entire narrative, thus following Cixous’ desire to repopulate a specific body of writing with the female voice and presence which was denied by the early North European poetic and narrative traditions7. Thus an element of queerness also operates, as the heroine enters a platonic relationship with another female character (which is cross-cultural and cross-racial8), providing a ‘fluid’, feminine “translation” of the traditionally ‘concrete’, masculine heroic figure. Therein we may also consider the potential likely audience for such a work: a society (fictional) in which heroic female characters exist and are celebrated – thereby drawing attention to the absence of such in historical literature.

Starting up almost where Beowulf ends, a terrible dragon ravages a land, forging a chain of apocalyptic events. Borges writes “the dragon is...the least fortunate of fantastic animals. It seems childish to us and usually spoils the stories in which it appears...however...we are dealing with a modern prejudice, due perhaps to a surfeit of dragons in fairy-tales9.” The purpose of my dragon is to upset the expectation of such beings existing solely to glorify the ego of male heroic types, and to present dragonkin as a species superior to all earthly races – thereby subverting the very structures upon which such legends tend to be predicated, and inverting the human-centric view of non-human life10.

In addition, the dragon and its kin are embedded components of the mythical culture presented through the lens of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s ‘monster theory’, which seeks to read “cultures from the monsters they engender11”, with the monster as “construct and projection [which] exists only to be read12” - a system which suggests Colonial and Othering strategies, especially when projected onto ‘exotic’ cultures. Borge’s view that the “dragon’s image [has something that] fits man’s imagination13” corresponds to Levi-Strauss’ theory that myths, contrary to Jungian archetypal collectivity, concern the “symbolic efficacy” of representing specific circumstances and concerns through a chosen set of symbols. In this sense my myth-making looks forward to a less divisive and prejudiced future reality by looking back through an alternative mythical history, one in in which humanity is not the centre of all creation. Unlike Tolkien, who set out to create a work (The Lord of the Rings) dedicated to “[his] country, England”, I hope to create one that is more universal, with themes of gender, ecology, moral philosophy and cosmic pessimism that resonate for a mixed 21st century audience.

1 Compound words, mini-riddles in fact, common to Old Norse and Old English poetry. e.g. hron-rade, ‘the whale’s road’ = ‘the ocean’ (Beowulf).

2 Discussed at length within In the Dust of This Planet in terms of dark ecology, cosmic pessimism and the supernatural

3 Being also the title of an OE poem, whose refrain translates as ‘as that passed, so shall this’, and, in its poetic meaning of ‘bold, brave’, is the name of my feline heroine’s father, whose influence frames her destiny in a classic narrative of Jungian, and Joseph Campbell-influenced, individuation.

4 See B. Lincoln, Death War & Sacrifice (pp. 231-268) on Dumezil’s possible ideological leanings, which may have informed his otherwise groundbreaking and highly influential mytho-cultural theories.

5 H. Cixous, K. Cohen and P. Cohen; ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, Signs , Summer, 1976, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Summer, 1976), pp. 875-893. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173239, accessed 15/5/21.

6 S. Vanherpen, ‘Remembering Auðr/Unnr djúp(a)uðga Ketilsdóttir: Construction of Cultural Memory and Female Religious Identity’, ed. K. Kanerva & E. Rasanen, Mirator 14 (2013):2, p. 3, www.glossa.fi/mirator/index_en.html, last accessed 29/4/21.

7 Notwithstanding the genre of Frauenlieder, or the popular tradition of ‘women’s songs’: the ‘epic tradition’ tends to embody John Berger’s view of Classical art generally that ‘men act, women appear’.

8 An integral concept suggested by queer theory readings of Beowulf, which interpret aspects of the relationship between Beowulf and King Hrothgar as potentially homoerotic. See B. Price, Potentiality and Possibility: An Overview of Beowulf and Queer Theory, Neophilologus (2020), 104:401–419 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11061-020-09636-8, last accessed 25/2/21.

9 The Book of Imaginary Beings, p. 154. (cf. J.R.R. Tolkien's defence of Beowulf’s critically chided ‘marginal elements which are given centre-stage’ [i.e. the monster battles] and his conviction that Beowulf’s dragon is the perfect – if not indeed the only – suitable doom for such a hero, “a thing made by imagination for just such a purpose. Nowhere does a dragon come in so precisely where he should”. (J.R.R. Tolkien (ed. Christopher Tolkien), The Monsters & the Critics; p. 31)).

10 This also continues my theme of rehabilitating unjustly maligned creatures, namely snakes – which I explored in Semester 2’s work The Medusa Chronicles.

11 J.J Cohen, Monster Culture (Seven Theses) in From Monster Theory: Reading Culture (p. 3)

12 Ibid., (p. 4)

13 The Book of Imaginary Beings, p.14

Basically, the documentation of my 2021 final project for my MFAAH Master's degree.

“Myth is a type of speech” (R. Barthes, 'Myth Today' in Mythologies).

If my work has a narrative, then it is one of narrative itself – sometimes multiple narratives, sometimes competing, unreliable, questioning, contradictory, and ambiguous. At times, meta-narratives; stories within stories, inside re-tellings of tales perhaps familiar or else new. And one of my most cherished kinds of ambiguous narrative is myth.

Myth, as an oral body of knowledge initially, is therefore speech. And in written form, embedded, it is capable of being analysed, quoted, paraphrased, interpreted, mis-interpreted, bastardized and corrupted.

The language I use to disclose my myth-makings are related, though separate; at once distant and unknowable, yet simultaneously tangible and everyday: English, and its antecedent, Old English – in which copious amounts of our modern English (and Scots – being of shared Germanic heritage) words originate, providing a bridge of familiarity to an unfamiliar culture.

In Old English literature we find oral works committed to writing – the final and only knowable forms that we, 1000 years later, have to analyse: “To the Anglo-Saxons, stories, riddles, songs – the wisdom of a people – was carried mentally, orally, in the word-hoard or ‘treasure house’ of words, the individual and collective memory of the tribe” (Craig Williamson, swarthmore.edu). In the writing I am producing, real language blends with mythical language – the speech of imaginary tribes and beings – as well as the language of myth, where tales of gods and heroines are woven into the ambitious narrative.

Namely, a work of epic poetry, simultaneously subversive to the conventions of that form yet also respectful of its representatives; and a mythographical, iconographical series of images of how the inhabitants of that poem’s world might have imagined their cosmos. Written in modern English, the poem presents itself as might a translation of a genuine text, with claims to keeping the tone and poetry of the original – the use of kennings1 proliferates with the brevity and qualities of allusion, double-meaning and the ambiguity inherent in Old English.

Dressed up as ‘high fantasy’, it nonetheless addresses real-world contemporary matters: gender roles, non-binary selfhood, eco-criticism, propaganda, historical colonization, the ‘world for itself’ and ‘world without us’ theories of Eugene Thacker2, and how historical narratives, and therefore the present, are (re)constructed. The poem plays with mythology; poems interpolate into the main narrative; characters bear multiple names; ‘point of view’ is a mobile concept. Recurring themes include the need for unity and exogamy – a critical source of myth as discussed by Levi-Strauss and Freud, via the incest taboo.

As the framework of the poem is an artificially-constructed myth system, this gives rise to visual representations of gods. Levi-Strauss describes ‘primitive’ art as a system of signifiers which connects the tribe to its supernatural beliefs, and which limited tools and materials can construct only as a visual language for its originating culture. My designs are amalgams of the local (Pictish stone carving) and Old English manuscript illumination, with aspects of native American and Mesoamerican representation in an attempt to evoke a tangible yet foreign culture. One example is the primal beast who is dismembered to create the cosmos and later restored as two separate creatures, who then beget all animal life [see Illustration 1]. This creation myth gives animals their separate and parallel genesis, allowing animal nature to live ‘for itself’, in reference to Thacker. These designs are modelled on the Pictish ‘beast’ which has been variously identified as giraffe, elephant, fish, kelpie, dolphin and horse [see Illustration 2]– its very ambiguity informing my use of it as a universal. My beast’s deer-like form is a reference to the OE deor3, which became ‘deer’, but originally referred to any wild animal.

Language itself becomes narrative; the poet’s rendering is, like any retelling, faulty by definition and cannot render unto us the calligraphic sweep of the Rockcats’ Sli’ith, or the physicality of Ulfish rune-carving. Borge’s Garden of Forking Paths reminds us of the power of the editorial voice, which even supersedes that of the narrator’s. Speech becomes mythical: ancient characters converse in a tongue drawn from Proto-Indo-European lexicons (namely Julius Pokornoy’s compendium). The shamanic storm god, Hrefni, owes his name to the OE word for ‘raven’ - simply a reflection of the poet’s own cultural and linguistic origins for the raven features in multiple world mythologies as a semi-divine solar messenger, and is a culture hero to the eastern forest native Americans. In reality, shamanism originates in Northern Asian and Ural-Altaic regions; thus Hrefni may himself be a migrant from distant tundra. Disregarding Georges Dumezil’s Indo-European tripartite structure4, my divine lineage is rather a spectrum of light to dark in which the goddess of the sun comes first, and whose centrepoint is hermaphroditic Hretha (a subconscious re-imagining of Eliphas Levi’s Baphomet – [illustrations 3 & 4]) and who is cited via ‘they/them’ pronouns (cf. William Blake’s ‘Ololon’ who is also referred to in such terms).

CONCEPTUAL AND THEORETICAL REFERENCES

After Semester 2’s intense studies of real myth, I set out to create a mythology of my own. To carry this, I chose the epic poem as a vehicle; ostensibly a tale of grand battles and heroic destinies, but via a world-view that embodies alternative and subversive modes of thinking, encouraging the reader to think laterally, and reconsider attitudes taken for granted in our world: Who owns land? Whose history (or mythology) is ‘right’? Why do we assume our morality is the correct one, and what is our place in the cosmos? What can legends and literature tell us about their tellers, and ourselves?

My S2 Humanities module Old English Texts heavily informed this work: themes of exile, loyalty, elegy and dream-vision in OE poetry gave me a literary corpus to ground myself in and ultimately take flight from, with analogues in The Exile of Guthlac, The Wanderer, The Ruin and Beowulf so that the work becomes symbolic of the cultural and literary mindset which devised that corpus. Through the ‘heroic’ poetic model – born from the hypermasculine comitatus culture of the Germanic mind, I re-colonise the world of the epic with characters and events counter to later propagandistic distortions of these aspects of English (and north European) literary heritage. The setting presents a world that is at first familiar: kings rule, men glorify battle, and swords are treasured heirlooms, but how might this world be viewed through the eyes of a non-human, non-male, non-heroic character, who – through fate – is nonetheless called to become heroic? The poem takes up the challenge of Cixous’ manifesto of écriture feminine: “Woman must write her self: must write about women and bring women to writing, from which they have been driven away as violently as from their bodies... Woman must put herself into the text – as into the world and into history – by her own movement5”. Female characters in the Germanic heroic canon tend to be presented as either passive peace-weavers (Wealhþeow) or as baneful disruptors of the comitatus (Modþryðo, Grendel’s mother): “The image of Old Norse women...can often be reduced to a simple dichotomy of ‘powerless’ and ‘powerful’, ‘good’ and ‘evil’...6” and whilst not myself female, I aim to create a number of nuanced female characters, the like of whom never appeared in actual heroic epics and whose actions drive the entire narrative, thus following Cixous’ desire to repopulate a specific body of writing with the female voice and presence which was denied by the early North European poetic and narrative traditions7. Thus an element of queerness also operates, as the heroine enters a platonic relationship with another female character (which is cross-cultural and cross-racial8), providing a ‘fluid’, feminine “translation” of the traditionally ‘concrete’, masculine heroic figure. Therein we may also consider the potential likely audience for such a work: a society (fictional) in which heroic female characters exist and are celebrated – thereby drawing attention to the absence of such in historical literature.

Starting up almost where Beowulf ends, a terrible dragon ravages a land, forging a chain of apocalyptic events. Borges writes “the dragon is...the least fortunate of fantastic animals. It seems childish to us and usually spoils the stories in which it appears...however...we are dealing with a modern prejudice, due perhaps to a surfeit of dragons in fairy-tales9.” The purpose of my dragon is to upset the expectation of such beings existing solely to glorify the ego of male heroic types, and to present dragonkin as a species superior to all earthly races – thereby subverting the very structures upon which such legends tend to be predicated, and inverting the human-centric view of non-human life10.

In addition, the dragon and its kin are embedded components of the mythical culture presented through the lens of Jeffrey Jerome Cohen’s ‘monster theory’, which seeks to read “cultures from the monsters they engender11”, with the monster as “construct and projection [which] exists only to be read12” - a system which suggests Colonial and Othering strategies, especially when projected onto ‘exotic’ cultures. Borge’s view that the “dragon’s image [has something that] fits man’s imagination13” corresponds to Levi-Strauss’ theory that myths, contrary to Jungian archetypal collectivity, concern the “symbolic efficacy” of representing specific circumstances and concerns through a chosen set of symbols. In this sense my myth-making looks forward to a less divisive and prejudiced future reality by looking back through an alternative mythical history, one in in which humanity is not the centre of all creation. Unlike Tolkien, who set out to create a work (The Lord of the Rings) dedicated to “[his] country, England”, I hope to create one that is more universal, with themes of gender, ecology, moral philosophy and cosmic pessimism that resonate for a mixed 21st century audience.

1 Compound words, mini-riddles in fact, common to Old Norse and Old English poetry. e.g. hron-rade, ‘the whale’s road’ = ‘the ocean’ (Beowulf).

2 Discussed at length within In the Dust of This Planet in terms of dark ecology, cosmic pessimism and the supernatural

3 Being also the title of an OE poem, whose refrain translates as ‘as that passed, so shall this’, and, in its poetic meaning of ‘bold, brave’, is the name of my feline heroine’s father, whose influence frames her destiny in a classic narrative of Jungian, and Joseph Campbell-influenced, individuation.

4 See B. Lincoln, Death War & Sacrifice (pp. 231-268) on Dumezil’s possible ideological leanings, which may have informed his otherwise groundbreaking and highly influential mytho-cultural theories.

5 H. Cixous, K. Cohen and P. Cohen; ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, Signs , Summer, 1976, Vol. 1, No. 4 (Summer, 1976), pp. 875-893. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3173239, accessed 15/5/21.

6 S. Vanherpen, ‘Remembering Auðr/Unnr djúp(a)uðga Ketilsdóttir: Construction of Cultural Memory and Female Religious Identity’, ed. K. Kanerva & E. Rasanen, Mirator 14 (2013):2, p. 3, www.glossa.fi/mirator/index_en.html, last accessed 29/4/21.

7 Notwithstanding the genre of Frauenlieder, or the popular tradition of ‘women’s songs’: the ‘epic tradition’ tends to embody John Berger’s view of Classical art generally that ‘men act, women appear’.

8 An integral concept suggested by queer theory readings of Beowulf, which interpret aspects of the relationship between Beowulf and King Hrothgar as potentially homoerotic. See B. Price, Potentiality and Possibility: An Overview of Beowulf and Queer Theory, Neophilologus (2020), 104:401–419 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11061-020-09636-8, last accessed 25/2/21.

9 The Book of Imaginary Beings, p. 154. (cf. J.R.R. Tolkien's defence of Beowulf’s critically chided ‘marginal elements which are given centre-stage’ [i.e. the monster battles] and his conviction that Beowulf’s dragon is the perfect – if not indeed the only – suitable doom for such a hero, “a thing made by imagination for just such a purpose. Nowhere does a dragon come in so precisely where he should”. (J.R.R. Tolkien (ed. Christopher Tolkien), The Monsters & the Critics; p. 31)).

10 This also continues my theme of rehabilitating unjustly maligned creatures, namely snakes – which I explored in Semester 2’s work The Medusa Chronicles.

11 J.J Cohen, Monster Culture (Seven Theses) in From Monster Theory: Reading Culture (p. 3)

12 Ibid., (p. 4)

13 The Book of Imaginary Beings, p.14

|

Illustration 2: Pictish beasts – from the Strathmartine Stone, and beast schematic |

|

Illustration 4: Mock stone carving of Hretha on stone at Cregennan - the Welsh association via the Ylfu (elf-like) people whose literature is modelled on medieval Welsh bardic traditions |

Comments

Post a Comment