Who Owns the Land? (reflections upon Chapter XXIV)

(A change to today's planned post, since for some reason Blogger (Google) has chosen not to allow me to upload any images. Instead, some written reflections upon one of the themes during the main narrative - that of the land itself, not just specifically of the small, mythical nation 'Gyldland' of the title, but of all land everywhere - including ours.)

The title of chapter XXIV, ‘The Visitors’, is a deliberate ploy: at first, as it is presented, a trio of hostile animal and bird-headed spirit-beings announce themselves to King Hodar’s camp at night in a blaze of baneful light, bearing dire warnings. Yet as the chapter concludes, it is clear who the real ‘visitors’ truly are – the heroes themselves, and by extension all sentient races, who have merely ‘lease’ upon the land which has been defended and guarded by these nature spirits ‘since day first dawned’. The lives of kings and heroes are temporal – the land is eternal, and so its guardians. While rather unfairly picking upon the heroes for their tree-felling activities in the course of their camp-building, given the wrack and ruin to which Gyldland has so far been subjected through battles, sieges and Skroth’s rampaging, we suspect this is the final straw for the spirits. They demand sacrifice for their tolerance, the details of which are left up to the heroes:

“We’ll seal this pact, if you will give

a sacrifice unto the earth.

For us alone; not gods, nor war,

nor gain nor glory – but something dear,

of value true. Prove your loyalty

to the land...”

At first flummoxed, King Hodar and Sigfri (the king’s seer, poet and advisor) are trumped by the Ulfish lord Ffrehkk’s druid, Ka-hrarr, who cheerfully announces she will give two human slaves as payment. Sigfri is repelled but Hodar, ever the pragmatic, concedes that they have little else which will satisfy the spirits – and besides, a worthy sacrifice could mean the spirits may return to help the heroes in future, and in their dire situation they need all the help they can get. Ka-hrarr sets off to personally arrange the giving of a ‘young and well’ fertile pair of humans, male and female. The ritual itself is glossed over – Sigfri ushers Womba away, thus also sparing the reader the literally gory details. It is enough that it occurs. The point of the visitation is to startle the reader (as well as the characters – Sigfri included, who confesses to Womba “Sometimes, I fear, I forget the way of things” - as an immortal, he himself has buried his earliest memories of when sacrifice was widespread to appease the gods and spirits) into remembering how things once were, when human life (and death) was part of a wider cosmic order and not sundered completely from the world and its cycles, which millennia of human fairy-tales had determined had been created and fertilized purely for their convenience and pleasure. The spirits are, of course, nature incarnate – caring nothing for individuals, only for balance, for natural fairness. The same forces which create butterflies and roses, sends floods and wildfires – nature’s own equilibrium. It seems the sentient races have pushed the balance rather too far of late.

While the Ulfish readiness to sacrifice what are to them lesser beings is of a racialist, if not even threatening, character (reaffirming their superiority to their human allies and reminding them of their status), and Ka-hrarr rather too keen to exercise this show of power; the sacrifice is still required, and something must be delivered. The spirits’ concerns are merely those of reciprocation: as the earth has been wilfully damaged, raped, abused, so must payment in kind be extracted from those beings who would commit such acts. The spirits are not evil for demanding such (they only specify “something dear”) - merely asserting the required balance, to counter life with death (and therefore, rebirth – as the blood of the victims will, in a small and symbolic way, feed the land, and the animals who share it with the sentient races). That the spirits have grievance with humanity specifically is clear, however:

“These [human] tribes have cursed the earth more than any.

Their blood belongs beneath our feet.”

The message to modern-day readers is obvious, and the point of the episode to the heroes is to remind them that there are greater forces out there and also, that in battling monsters, they do not allow themselves to become equally monstrous. That the spirits condemn humanity over the Ulfhednaar, for all their fearsome reputation, historical conquests, and cruel customs (sacrifice, slavery) is significant – rockcats and humans may view themselves as culturally more ‘noble’ but the spirits have nothing to gain by appeasing Ka-hrarr and her people, as they “do not deal in names or tribes”, meaning all the sentient peoples are alike to them. Since the fall of the Iron Empire, the Ulfhednaar have lived their isolated way in the frozen realm of Evernight, leaving it to the other races and the dark hordes of destruction to continue the deforestation and abuse of the ‘middle-realm’. That the idea of the land, its fruits and forests being merely ‘leased’ to the sentient tribes who dwell upon it, is made explicit several times, notably as Ka-hrarr exhorts the spirits thus:

“Great Land-lords, speak:

give unto us your judgement true.”

and the spirits reply, having accepted the offerings:

“As such, you may have lease to live

as you see fit...”

The rest of the pact is simple, as any tenant’s lease may be expected to be – keep the place in order, and you won’t be evicted (or worse). As they depart, the spirits present a magical horn to the heroes, which may be used to summon them for future aid. Sigfri collects the horn and exclaims:

“An ice-ox horn! Those beasts died out

great centuries ago. This is a thing of wonder.”

Namely, a relic of an extinct species – an ironic reminder of the irreversible effects of human (and other races’) actions.

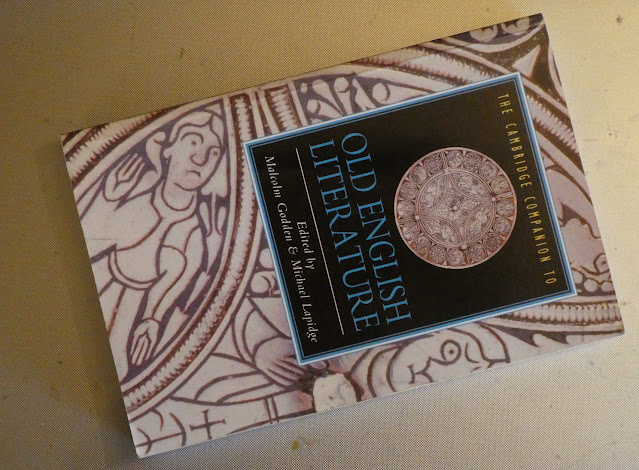

Background note: Much of this section (and subsequent continuations of the theme) were informed by Semester 1's Humanities readings on ecocriticism (autumn 2020), as well as talks on the nature of 'nature' itself and how it is often defined, sometimes vaguely, sometimes strictly, as something distinct and separate from humanity and civilisation; 'wilderness' being another problematic term, often suggesting a 'void' just waiting to be ploughed up by capitalistic industrial interests and fulfilling no useful purpose until such times. The spirits themselves are derived from the Old Norse landvaettir who were protectors of the land, with the ability to harm those who did not show it sufficient respect (see, e.g., R. Simek, A Dictionary of Northern Mythology, p.186). Some hints of 'dark ecology' began to sneak in at this point too, and continued to unfold into my later readings of the Old English depictions of hostile weather conditions and landscape, natural forms and forces without care for the 'earth-treaders' (cf. especially The Seafarer, which is deliberately alluded to in later passages, and also Beowulf, in, for example, the description of the Grendelmere, through which even hunted deer refuse to flee, choosing death instead). Eugene Thacker's concept of the 'world for itself' also began to show its influence, as most of Book II (to which this chapter belongs) was produced and revised through late 2020.

Comments

Post a Comment