Summarising the 'Gyldlandsaga' So Far...

In putting together the narration for a 'work in progres' disscussion of the project for tomorrow, I realised this made a decent summary of the project to date, including some new thoughts and research. So here goes:

And here is the text of the presentation (with a few extra explanatory points):

This project explores the relationship between word, image, object, and idea, and the representation of a non-existent place and time in a very specific space of bounded, physical place/time.

Deconstruction has become the theme of this project, via growing reference to the ideas of Derrida and Foucault, as well as a breakdown of binary oppositions, upon which much structuralist theory is founded - as well as certain social, cultural and political restrictions which persist today.

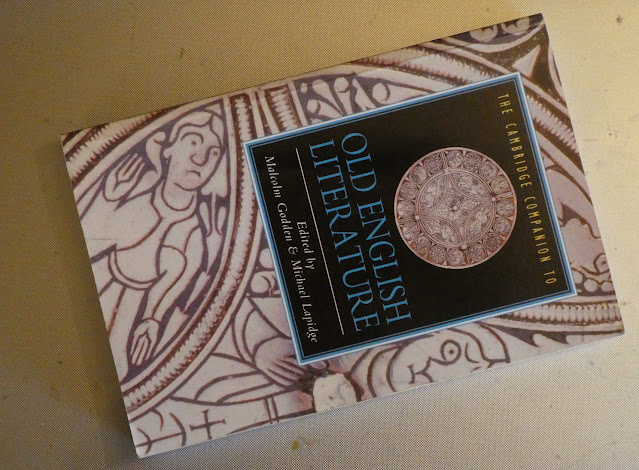

Originally influenced by the mythological research of levi-Strauss, it was created as a fictional myth system – a body of knowledge concerning gods, their origins, and tales – and their representations – both visual, in the form of archaeological ‘relics’ of a non-existent place and time, and also embedded as text, in a 75k word poetic narrative, influenced by the genre of the heroic epic in general, and works in the Old English corpus such as Beowulf, the Wanderer and other works studied in my choice of Semester 2 Humanities module.

In presentation, I reference Foucault’s idea of the heterotopia and its relevance to the museum, as an ordered space presenting knowledge and artefacts, as well as the ‘gaps which exist between the words and the images they describe’. The museum is not necessarily a privileging of Enlightenment-era theories of taxonomies, ordering and exclusion and acceptance, as pointed out by Beth Lord, of Dundee University, in her 2006 essay ‘Foucault’s Museum: difference, representation, and genealogy’. The idea of deconstruction was taken to its extreme by dismantling the display case intended to hold the ‘stone artefacts’ under glass, in traditional ‘look, don’t touch’ museum format. In this re-imagined museum, the stones are often left as they exist in nature, or as they may have been first found, after the dissolution of the culture which created and forgot about them. Notes and little essays to inform visitors of the purpose of these stones are given equal, if not higher, privileging, whilst the literal ‘embedding’ of language – written in stone, as well as printed – is rendered obscure (though translatable) through an invented set of rune-style characters.

The text itself, yet to be printed, is planned to be produced in a formal hardbacked binding, suggestive of the voice of authority, academic excellence, and accurate research. What the text contains is alleged to be a modern-day translation of an otherwise unknown epic narrative, describing hitherto unknown lands, nations, and races, in which the protagonist is neither male, nor even human. In this sense, the text deconstructs the fundamentals of the epic, whilst maintaining the essential universals of individuation, personal growth, learning, and the journey of life – and death – itself.

Semester 1’s Humanities classes also informed the sometimes radically divergent layout of the text, echoing visual poetry, in which negative space – so often missing from printed editions of ‘epics’ or long poems – is used sparingly but knowingly, with reference to the Eastern concepts of void as a positive, enhancing feature of art and nature, as opposed to a ‘nothing’ waiting to be filled by a ‘something’. My earlier studies of Taoism, and recent exploration of the Japanese idea of Ma, helped to inform these – as well as the ‘spaces between’, which are sometimes literal representations of gaps created between repeated, reversed designs. These non-binary gaps, sometimes recognisable, sometimes Rorscharch-like, echo the gaps which exist in Foucault’s depiction of the museum, and when reproduced at 50% opacity, exist visually in that literal ‘grey area’ between black and white. (As a shaman-figure, the culture hero and raven-god Hrefni himself also exists ‘beyond the binary’, as a being who mediates between worlds, and cross-genderism or transvestitism is also a noted feature of shamanic culture).

In the sense of giving centre stage to what are usually deemed ‘marginal’ elements in the text – female characters, monsters, non-human characters – a criticism once levelled at Beowulf and famously argued against by Tolkien in his essay The Monsters & the Critics – the assumed scholarly voice of the printed tome seeks to counter problematic readings and representations engendered and perpetuated by the privileged culture which created such authoritative – sometimes deliberately biased – constructions of history, literature, society and knowledge in general. However, the poem is anonymous – the title page refers to me as the ‘translator’ - but in what sense? As Gnaoimi Siemens writes in ‘Translating the ancient female voice as queer’, that “queer is political”, an underlying theme embedded in the narrative due to the Platonic relationship between the two main female characters which is same-sex and cross-cultural, as well as cross-racial. The unknowability of the true voice of the poet is deliberate. Mary Beard quotes Telemachus of the Odyssey in telling Penelope to shut up, and that “speech will be the business of men”, and we may recall that Homer’s writings were long regarded as invaluable sources of truth and knowledge far beyond their cultural and literary merit. Had the ancient female characters – and their voices – existed in reality, how might they have been translated – or mistranslated – by scholarly academics of the 18th and 19th Century? The museum notes on representations of the gods depicted in the stonework even suggests that scholarly attempts had deliberately reconstructed the order – assumed to be hierarchical – of the deities, which privileges the female sun-goddess over the male raven storm-god. This is inspired by real 19th C. patriarchal scholarship, which re-attributed the OE women’s poem ‘Wife’s Lament’ to a male hero, according to the prejudices of the time and perpetuated until as late as 1963 (see RC Bambas, in the Journal of English & Germanic Philology 62). Overall, this project hopes to serve as a deconstruction of various attitudes and strands that exist within scholarship itself as much as its representation and presentation to the public.

Comments

Post a Comment