Fragments and Intermediaries, Curating Discourse

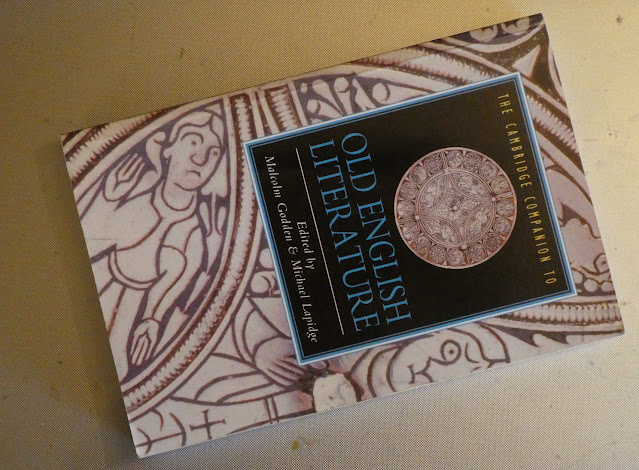

Yesterday, I collected the 5 copies of the printed, bound Gyldlandsaga books from the printers and examined them...it's always nerve-wracking to open up that first copy and peer inside at how it's turned out. But the books look very fine - they have good, solid (even monumental) weight and physicality, and the steel spine adds excellent durability. The lack of "real book" textualities such as copyright bibliographical data, page numbering, ISBN etc., I think, help to enforce the 'art object' aspect of them and take away the 'mass production' aspects of cataloguing and data storage: as far as the international records are concerned, this book does not exist as such (cf Hannah Arendt's idea of refugees with no identity papers etc. being classed as 'non-people by 'the authorities' - i.e those whose rules constitute being or non-being). All the Old English texts on which this is based exist only in unique manuscripts, allowing these very limited printed texts to therefore exist in a 'grey area' between uniqueness and ubiquity.

My plan for the books is to have 4 copies available for sale during the exhibition periods, and the one currently ensconced in the 'museum' space will become my own copy afterwards. Hand numbering and signing the other 4 may help to seal the 'artist's work' aspect of this very limited edition (or I may do that for them all, and keep #1 for myself)...

In the following tutorial, I was able to explain the whole project and discuss the more sculptural aspects of the work - from 'ancient' means of creating artwork/sculptural pieces (the stones) contrasted to the 'modernist' (the deconstructed museum), and how the various 'fragments' relate to each other, and how the viewer is invited to interact with them all.

The glass lid upright provoked some discussion, and we agreed that having something underneath it helped to fulfil a partial purpose - it still 'protects' a part of the exhibition, but now a couple of printed explanatory texts. The Whitney museum typeface used in the 'Do not touch!' warning will be mirrored by a 'Please Touch' sign above the book display. The texts underneath the glass embed language - in the sense that museums tend to embed a single narrative for visitors, an accepted, standard view of what they present, even if what is on show is mere fragments, and not just through the words used but by the arrangement and juxtaposition of exhibits, too. In a sense, this show is also about archaeology, on various levels - in the sense that Foucault applies to it in The Archaeology of Knowledge, wherein discontinuity erupts (a myth system and culture existing in isolation with reference only to what remains of it, and can therefore be assumed, or guessed - which is rather why I want to limit the 'real-world' connections in the explanatory texts), and the discursive meanings of statements: from the stern warning sign above to the entire 76,500 words of 'statement' in the bound texts - statements that refer to names, places, things and ideas that exist nowhere else, i.e without specific geographical, cultural, historical and individual realities. In this sense, these statements have no true discursive meaning in the sense of Foucault's Archaeology, as things presented in a mostly meaningful fashion in accordance with the basic tenets of public displays of knowledge and history (or which at least allege to be these things). At which point the notion of reality itself starts to break down, as here I am writing about things that don't exist, and yet they are being written about - and looked at (as engraved representations) in the museum, or read about - and therefore forming thought/sense-perceptions in the minds of viewers and readers. As Foucault notes, "The book is not simply the object that one holds...its unity is variable and relative. As soon as one questions that unity, it loses its self-evidence; it...constructs itself, only on the basis of a complex field of discourse" (The Archaeology of Knowledge, Tavistock, Bristol, 1974).

The more I think about this project, the more complex and spiral-like (or labyrinthine...or serpentine) it seems to become, with its meandering network of sneaky real-world references, similarities, points of origin and points of digression. As we agreed at the tutorial, the work does not overturn entirely its own subect matter - the display remains somewhat recognisable as a kind of museum display...the book is a kind of epic...the book lectern is a kind of bookshelf - each still able to fit into some Platonic ideal box of what generally constitutes those things in terms of overall form and function (the book isn't random computer-generated gibberish, but weaves complex tales of heroic destinies fulfilled and multiple adventures; the display case isn't suspended from the ceiling by helium balloons, etc.). What these things do present, I think, is the 'gray area' or the spaces between what those descriptive terms 'officially' denote (epics are about brave human men, not reluctant feline women; display cases serve to protect and create a barrier to the viewer) and what they truly are. Intermediaries - like shamen (one of which is the first character described in the book, he who becomes the raven-god Hrefni), capable of existing with a foot in two worlds at the same time (or rather, by uniting the two within themselves, becoming a third model of being).

Might 'Intermediaries' be a title for the whole show..? It's the first time I've thought of such an idea. But it's a start.

Comments

Post a Comment